Welcome to our What is… series,

Autodesk revit for mac torrent. where we turn technical jargon into plain English.

Where we turn technical jargon into plain English. Phishing is the word used when a cybercriminal sends you some sort of electronic message to trick you into doing something insecure. The “fishing” metaphor refers to the idea of getting you on the hook and then reeling you in. And in late September, Sophos’ Managed Threat Response team assisted an organization in mitigating a Ryuk attack—providing insight into how the Ryuk actors’ tools, techniques and practices have evolved. The attack is part of a recent wave of Ryuk incidents tied to recent phishing campaigns.

Phishing is the word used when a cybercriminal sends you some sort of electronic message to trick you into doing something insecure.

The “fishing” metaphor refers to the idea of getting you on the hook and then reeling you in.

The crooks behind this sort of crime, who are known colloquially as phishers, usually use email, because it is surprisingly easy to mock up messages to look realistic.

But phishing attacks may also arrive via social media, SMS or other instant messaging platforms.

Here are some examples of the sort of treachery used by phishers:

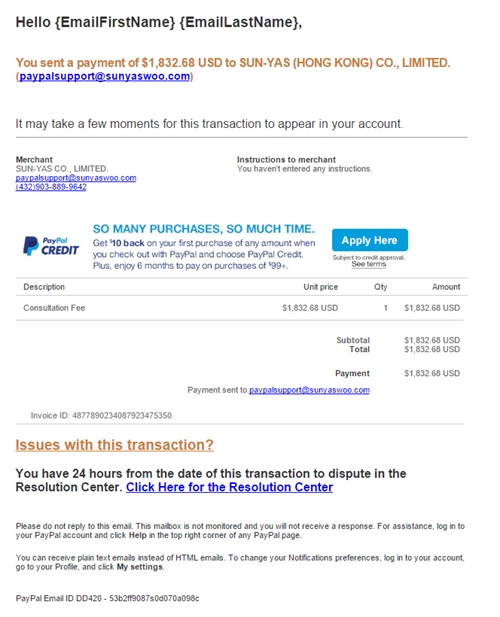

- You receive an invoice detailing a modest purchase from a well-known online site, complete with ripped-off logos and text copied from a genuine invoice. At the bottom is a legitimate-looking link or button to

[Contest this charge]or[Query this purchase]. You know you didn’t make the purchase, so your inclination is to click through and log in. But if you do, you end up on an imposter login page, and your password ends up in the hands of the crooks. - You receive an email from someone apparently applying for a job that’s currently advertised on your company website. Attached to the email is a file that looks like a document containing a CV (résumé). Your inclination is to open it, but if you do, you inadvertently run a booby-trapped file that allows the crooks to implant malware on your computer.

- You receive a marketing email inviting you to take a realistic-looking survey in return for a chance to win a shopping voucher, or an iPhone, or a holiday. Your inclination is to fill it in, but along the way you are asked to provide personal data that you would normally keep to yourself, such as your birthday, your home address or your credit card details.

What to do?

Phishing can be hard to spot, because phishers don’t always make telltale speeling errorrs or gammatrical misteaks.

The phishers may know your real name and address, so they don’t always start with giveaways like Dear Sir/Madam, or use a vague address such as Arizona.

Here are some tips to avoid getting sucked in:

- Don’t enter passwords into login pages that show up after you click on a link in an email. Bookmark the official login pages of your favourite sites, or type the URLs into your browser from memory.

- Avoid opening attachments in emails from recipients you don’t know, even if you work in HR or accounts and you use attachments a lot in your job.

- Set up an “ask the experts” email address inside your organisation, e.g.

security@example.com. That gives your users a quick way to ask for advice about unexpected emails and unsolicited attachments. - If in doubt, don’t give it out! Your personal data simply isn’t worth the vanishingly small chance of winning an iPad from a marketing company you’ve never heard of.

Phishing gets its curious spelling from a 1970s crime known colloquially as phreaking. Hackers figured out how to make free calls using a variety of illegal tricks to “freak out” the telephone system, for example by playing special musical tones down the line. Freaking the phone system morphed into phreaking, and by analogy, fishing for user’s passwords and other personal data became known as phishing.

Phishing – how this troublesome crime is evolving

Portable citrix receiver. Other ways to listen: download MP3, play directly on Soundcloud, or get it from iTunes.)

The operators of Ryuk ransomware are at it again. After a long period of quiet, we identified a new spam campaign linked to the Ryuk actors—part of a new wave of attacks. And in late September, Sophos’ Managed Threat Response team assisted an organization in mitigating a Ryuk attack—providing insight into how the Ryuk actors’ tools, techniques and practices have evolved. The attack is part of a recent wave of Ryuk incidents tied to recent phishing campaigns.

First spotted in August of 2018, the Ryuk gang gained notoriety in 2019, demanding multi-million-dollar ransoms from companies, hospitals, and local governments. In the process, the operators of the ransomware pulled in over $61 million just in the US, according to figures from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. And that’s just what was reported—other estimates place Ryuk’s take in 2019 in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Starting around the beginning of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, we saw a lull in Ryuk activity. There was speculation that the Ryuk actors had moved on to a rebranded version of the ransomware, called Conti. The campaign and attack we investigated was interesting both because it marked the return of Ryuk with some minor modifications, but also showed an evolution of the tools used to compromise targeted networks and deploy the ransomware.

The attack was also notable because of how quickly the attacks can move from initial compromise to ransomware deployment. Within three and a half hours of a target opening a phishing email attachment, attackers were already conducting network reconnaissance. Within a day, they had gained access to a domain controller, and were in the early stages of an attempt to deploy ransomware.

The attackers were persistent as well. As attempts to launch the attack failed, the Ryuk actors attempted multiple times over the next week to install new malware and ransomware, including renewed phishing attempts to re-establish a foothold. Before the attack had concluded, over 90 servers and other systems were involved in the attack, though ransomware was blocked from full execution.

Let the wrong one in

The attack began on the afternoon of Tuesday. September 22. Multiple employees of the targeted company had received highly-targeted phishing emails:

From: Alex Collins [spoofed external email address]

To: [targeted individual]

Subject: Re: [target surname] about debit

Please call me back till 2 PM, i will be in [company name] office till 2 PM.

[Target surname], because of [company name]head office request #96-9/23 [linked to remote file], i will process additional 3,582 from your payroll account.

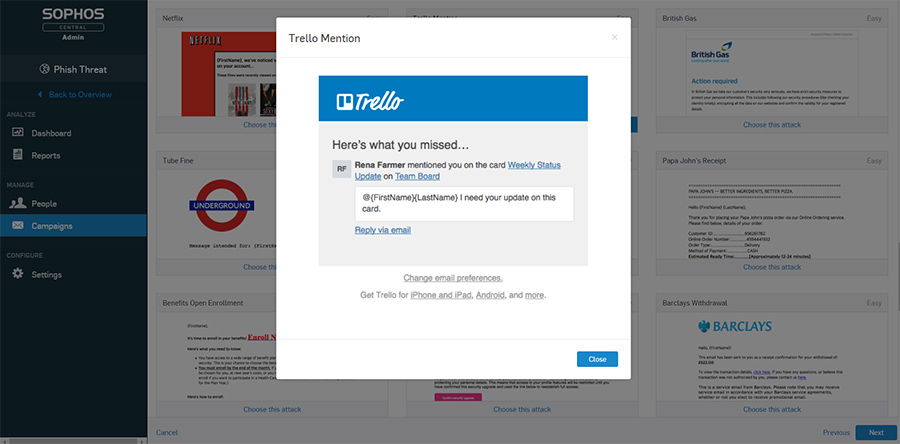

Sophos Phishing

[Target first name], call me back when you will be available to confirm that all is correct.

Here is a copy of your statement in PDF[linked to remote file]. Program for drawing on mac.

Alex Collins

[Company name] outsource specialist

The link, served up through the mail delivery service Sendgrid, redirected to a malicious document hosted on docs.google.com. The email was tagged with external sender warnings by the company’s mail software. And multiple instances of the malicious attachment were detected and blocked.

But one employee clicked on the link in the email that afternoon. The user opened the document and enabled its content, allowing the document to execute print_document.exe—a malicious executable identified as Buer Loader. Buer Loader is a modular malware-as-a-service downloader, introduced on underground forums for sale in August of 2019. It provides a web panel-managed malware distribution service; each downloader build sold for $350, with add-on modules and download address target changes billed separately.

In this case, upon execution, the Buer Loader malware dropped qoipozincyusury.exe, a Cobalt Strike “beacon,” along with other malware files. Cobalt Strike’s beacon, originally designed for attacker emulation and penetration testing, is a modular attack tool that can perform a wide range of tasks, providing access to operating system features and establishing a covert command and control channel within the compromised network.

Over the next hour and a half, additional Cobalt Strike beacons were detected on the initially compromised system. The attackers were then able to successfully establish a foothold on the targeted workstation for reconnaissance and to hunt for credentials.

A few hours later, the Ryuk actors’ reconnaissance of the network began. The following commands were run on the initially infected system:

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C whoami /groups (accessing list of AD groups the local user is in)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C nltest /domain_trusts /all_trusts (returns a list of all trusted domains)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C net group “enterprise admins” /domain (returns a list of members of the “enterprise admins” group for the domain)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32net1 group “domain admins” /domain (the same, but a list of the group “domain admins”)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C net localgroup administrators (returns a list of administrators for the local machine)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C ipconfig (returns the network configuration)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C nltest /dclist:[target company domain name] (returns names of the domain controllers for the company domain name)

- C:WINDOWSsystem32cmd.exe /C nltest /dclist:[target company name] (the same, but checking for domain controllers using the company name as the domain name)

Forward lateral

Using this data, by Wednesday morning the actors had obtained administrative credentials and had connected to a domain controller, where they performed a data dump of Active Directory details. This was most likely accomplished through the use of SharpHound, a Microsoft C#-based data “injestor” tool for BloodHound (an open-source Active Directory analysis tool used to identify attack paths in AD environments). A data dump from the tool was written to a user directory for the compromised domain administrator account on the domain server itself.

Another Cobalt Strike executable was loaded and launched a few hours later. That was followed immediately by the installation of a Cobalt Strike service on the domain controller using the domain administrator credentials obtained earlier. The service was a chained Server Message Block listener, allowing Cobalt Strike commands to be passed to the server and other computers on the network. Using Windows Management Interface, the attackers remotely executed a new Cobalt Strike beacon on the same server.

In short order, other malicious services were created on two other servers using the same admin credentials, using Windows Management Instrumentation from the initially compromised PC. One of the services configured was an encoded PowerShell command creating yet another Cobalt communications pipe.

The actors continued to perform reconnaissance activities from the initially infected desktop, executing commands trying to identify potential targets for further lateral movement. Many of these repeated previous commands. The nltest command was used in an attempt to retrieve data from domain controllers on other domains within the enterprise Active Directory tree. Other commands pinged specific servers, attempting to gain IP addresses. The actors also checked against all mapped network shares connected to the workstation and used WMI to check for active Remote Desktop sessions on another domain controller within the Active Directory tree.

Setting the trap

Late Wednesday afternoon—less than a day after the victim’s click on the phish— the Ryuk actors began preparations to launch their ransomware. Using the beachhead on the initially compromised PC, the attackers used RDP to connect to the domain controller with the admin credentials obtained the day before. A folder named C:Perflogsgrub.info.test2 – Copy was dropped on the domain controller— a name consistent with a set of tools deployed in previous Ryuk attacks. A few hours later, the attackers ran an encoded PowerShell command that, accessing Active Directory data, generated a dump file called ALLWindows.csv, containing login, domain controller and operating system data for Windows computers on the network.

Next, the SystemBC malicious proxy was deployed on the domain controller. SystemBC is a SOCKS5 proxy used to conceal malware traffic that shares code and forensic markers with other malware from the Trickbot family. The malware installed itself (as itvs.exe), and created a scheduled job for the malware, using the old Windows task scheduler format in a file named itvs.job—in order to maintain persistence.

Sophos Phish Threat Datasheet

A PowerShell script loaded into the grub.info.test folder on the domain controller was executed next. This script, Get.DataInfo.ps1 , scans the network and provides an output of which systems are active. It also checks which AV is running on the system.

The Ryuk actors used a number of methods to attempt to spread files to additional servers, including file shares, WMI, and Remote Desktop Protocol clipboard transfer. WMI was used to attempt to execute GetDataInfo.ps1 against yet another server.

Failure to launch

Thursday morning, the attackers spread and launched Ryuk. This version of Ryuk had no substantial changes from earlier versions we’ve seen in terms of core functionality, but Ryuk’s developers did add more obfuscation to the code to evade memory-based detections of the malware.

The organizational backup server was among the first targeted. When Ryuk was detected and stopped on the backup server, the attackers used the icacls command to modify access control, giving them full control of all the system folders on the server.

They then deployed GMER, a “rootkit detector” tool:

GMER is frequently used by ransomware actors to find and shut down hidden processes, and to shut down antivirus software protecting the server. The Ryuk attackers did this, and then they tried again. Ryuk ransomware was redeployed and re-launched three more times in short order, attempting to overwhelm remaining defenses on the backup server.

Ransom notes were dropped in the folders hosting the ransomware, but no files were encrypted.

In total, Ryuk was executed in attacks launched from over 40 compromised systems,but was repeatedly blocked by Sophos Intercept X. By noon on Thursday, the ransomware portion of the attack had been thwarted. But the attackers weren’t done trying—and weren’t off the network yet.

Sophos Phishing Cost

On Friday, defenders deployed a block across the domains affected by the attack for the SystemBC RAT. The next day, the attackers attempted to activate another SOCKS proxy on the still-compromised domain controller. And additional Ryuk deployments were detected over the following week—along with additional phishing attempts and attempts to deploy Cobalt Strike.

Lessons learned

The tactics exhibited by the Ryuk actors in this attack demonstrate a solid shift away from the malware that had been the basis of most Ryuk attacks last year (Emotet and Trickbot). The Ryuk gang shifted from one malware-as-a-service provider (Emotet) to another (Buer Loader), and has apparently replaced Trickbot with more hands-on-keyboard exploitation tools—Cobalt Strike, Bloodhound, and GMER, among them—and built-in Windows scripting and administrative tools to move laterally within the network. And the attackers are quick to change tactics as opportunities to exploit local network infrastructure emerge—in another recent attack Sophos responded to this month, the Ryuk actors also used Windows Global Policy Objects deployed from the domain controller to spread ransomware. And other recent attacks have used another Trickbot-connected backdoor known as Bazar.

The variety of tools being used, including off-the-shelf and open-source attack tools, and the volume and speed of attacks is indicative of an evolution in the Ryuk gang’s operational skills. Cobalt Strike’s “offensive security” suite is a favorite tool of both state-sponsored and criminal actors, because of its relative ease of use and broad functionality, and its wide availability—“cracked” versions of the commercially-licensed software are readily purchased in underground forums. And the software provides actors with a ready-made toolkit for exploitation, lateral movement, and many of the other tasks required to steal data, escalate the compromise and launch ransomware attacks without requiring purpose-made malware.

Sophos Pricing

While this attack happened quickly, the persistence of the attacks following the initial failure of Ryuk to encrypt data demonstrate that the Ryuk actors—like many ransomware attackers—are slow to unlatch their jaws, and can persist for long periods of time once they’ve moved laterally within the network and can establish additional backdoors. The attack also shows that Remote Desktop Protocol can be dangerous even when it is inside the firewall.

IOCs for this attack are posted on the SophosLabs GitHub here.

Sophos Phishing Tool

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge the contributions of Peter Mackenzie, Elida Leite, Syed Shahram and Bill Kearney of the MTR team, and Anand Aijan, Sivagnanam Gn, and Suraj Mundalik of SophosLabs to this report.